Mobility. First we crawl. Then we walk, and then we run. Later we bike, drive and even fly.

Mobility. First we crawl. Then we walk, and then we run. Later we bike, drive and even fly.

With each of our mobile milestones, our world expands and with it, our minds.

This is the human narrative of mobility – the causal relationship between pushing the limits of our physical reach and the personal growth and empowerment that it brings to us.

So many of us remember when we first rode a bike, when we got our driver’s license, when we went away to school. These are thresholds through which we passed, allowing us to emerge into entirely new and expanded worlds.

These were our indelible moments of empowerment – windfalls of freedom that made us feel most alive and in command of our destiny.

My first job out of college was with Delta Air Lines. It was the hardest job I’ve ever had – taking reservations in a 600 person call center, on the night shift and through holidays, in New York City at a time when it wasn’t so great to be in New York City. It was pre-internet, of course, when each of us were the functional equivalent of the machinery that hadn’t yet been invented, on the clock taking hundreds of calls a night.

The upside: I could fly for free, anywhere at almost any time. I could fly to a beach in Florida in the dead of winter, for the day. I could go to Europe for a weekend. I could fly to a Giants-Cowboys game on a Sunday morning and be back that night. It was intoxicatingly empowering – a degree of mobility that literally made the entire world accessible to me.

The relationship between mobility and empowerment is universal, but while empowerment in the developed world refers to things we want, in other parts of the world it is a matter of life and death need: the simple access to things like water and medical care. Without sufficient mobility, the most basic form of empowerment – the power to survive – is up for grabs.

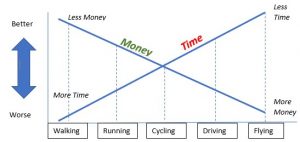

Throughout the world, unless you are from a nation of relative wealth (or work for an airline), mobility can be expensive. Generally – and based on the premise that time is money – there is a higher cost for greater mobility.

Walking is cheap, flying isn’t, and for everything in between there is a value exchange that is made – sometimes voluntarily, other times not – between how fast and far one can go with a particular mode of transportation and how much it costs.

This raises the question: if we consider all of humanity, which mode of transportation delivers the most net value to the largest number of people in the entire world?

Our personal answer to that question is often geographically and “infrastructurally” determined. If I am back in New York, it’s probably the subway.

But what about the world as a whole? What is the optimal cost-benefit method of getting from point A to point B, not if you are rich or live in New York City, but if you are an average citizen of the world?

Based on that highly technical resource of information known as common sense, my rudimentary graph makes the case that humankind’s optimal mode of transportation, in which the relationship between time and money is optimized, is a bicycle.

Naturally, cost is lowest, and therefore most accessible, for all human powered transportation, and benefit is highest for whatever human powered transportation can most efficiently convert that power into mobility. The fact that cycling is where Time and Money intersect is the simple explanation for why somewhere around 2 billion people on earth ride a bike, and it also explains why there are numerous non-profits committed to delivering the crucial benefit of mobility via bicycles.

Mobility is both a basic human need and a physical manifestation of curiosity, which itself is the engine of personal, intellectual and often economic growth. We take mobility for granted in the developed world because so many of our basic human needs are already satisfied.

But many of the various “mobility battles” around the world are actually battles for human rights. This is most obvious to anyone with a disability, but these battles also often hinge on gender.

For example, women in Saudi Arabia were only recently given the permission to drive a car and even now, there are still activist women in that “kingdom” who have been imprisoned for basically driving while female.

Denying mobility to women has a long history around the world in various cultures as a form of control and mysogny. Without mobility, there is no power, and this tactic directly extends to the realms of economic and intellectual mobility.

One of my heroes is Nobel prize winner Malala Yousafzai, or simply, Malala, as many of us know her. Malala was shot in the head for pursuing that form of intellectual mobility we know of as an education. Disturbingly, there are still places in the world where the mobility of women, in any form, is seen as a threat to the ruling gender.

On the positive side, bicycles in developing countries are not just a physical means to get to work; in many cases, they are the work for entrepreneurial couriers, messengers and taxi drivers.

On the positive side, bicycles in developing countries are not just a physical means to get to work; in many cases, they are the work for entrepreneurial couriers, messengers and taxi drivers.

Meanwhile, in America, we face our own mobility challenges, where the cost of mobility, and the barriers to accessing it are an increasing concern.

The environmental cost of mobility must now be built into the analysis of all modes of transportation, but there is also the corporate mobility of women into leadership positions, the economic mobility that is being suppressed by unequal pay, and the educational mobility that has yet to fully take flight for girls with an interest and aptitude for the STEM fields. These are challenges that must be confronted head on.

America’s ethos of freedom and opportunity is inextricably tied to a belief in the basic human right to mobility. Whether our ancestors were crossing the ocean (willingly), or going west in search of their own prosperity, the desire to see what’s beyond the horizon is in our DNA – as much a part of our culture as it is a reason for our success.

The genius of bicycles, the importance of equality, the spirit of America – all of this comes together to make the case for the mission of the Tour of America:

Mobility is synonymous with freedom and for that reason most of all, it is an essential part of the American spirit, which is why cycling as a form of literal mobility is an ideal metaphor for the intellectual and economic promise of mobility that gives us the opportunity to thrive as individuals.

Our mission is admittedly aspirational – there is much to do to live up to this promise, and not just for women – but it is also well within our capabilities.

All we need to do is mobilize.